RiverWise

Issue 31 ~ April 2021

The monthly newsletter of the Lower Breede River Conservancy Trust

Have you renewed your

boat licence yet?

Annual Municipal Boat licenses are due for renewal every year from 1 July and valid until 30 June the following year.

Just a reminder of our outlets available for boat license sales for 2020/2021

MALGAS OUTLET:

Living the Breede

Phone: 067 162 9081 or 082 324 2757

Open: Mon-Sun from 08:00 - 17:00

RIVERINE OUTLET:

Breede Riverine Estate

Phone: 028 542 1345

Open: 09:00 – 17:00

WITSAND OUTLETS:

Lower Breede River Conservancy Office

Phone: 028 537 1296

Open: Mon-Fri 08:00 - 16:00

Sands Supermarket

Phone: 028 537 1800

Open: 09:30 - 16:30

Nella se Winkel

Phone: 028 537 1304

Open: 07:30 - 17:30

SWELLENDAM OUTLET:

Heyneman Yamaha

Phone: 028 514 2010

Open: 08:00 – 17:00

Infanta Inflatables

Phone: 028 514 1589

Hours:

08:00 - 17:00 Monday to Thursday

08:00 - 16:00 Friday, Closed Weekends

ONLINE LICENSES:

Buy your boat license online and arrange to pick up your disk at Living the Breede (Malgas) or LBRCT office (Witsand)

https://breede-river.org/licences/

Contact our office if you have any questions regarding the boat licenses - 028 537 1296 / info@breede-river.com

What we have been up to

In this issue

April has been another eventful month. We started the month conducting operations with CapeNature over the Easter weekend. Five loggerhead turtles were rescued the following week. We assisted the Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (DEA&DP) with their water sampling, as well as conducted our own water quality run and bird count. In this issue we have written a long article on the different tortoises, turtles and terrapins of the lower Breede River area. Jetty and slipway policies are summarised, and the illegal removal of indigenous milkwoods are revisited. We have also included a list of indigenous trees which can be used instead of popular alien trees.

Operations

The LBRCT worked alongside CapeNature to enforce the Marine Living Resources Act of 1998. This act is set out to protect marine ecosystems, reduce overexploitation and ensure the long-term sustainability of living resources in South African oceans. In 2013 the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) published regulations on fishing at night on the Breede River estuary. The Night Fishing Ban states that no person may fish in the estuary between the hours of 20:30 and 05:00 of the following day. The Breede River is an ecologically sensitive estuary as it is an important breeding ground for many freshwater and marine linefish species. Hence the objective of this regulation to the MLRA is to further protect these species.

CapeNature and the LBRCT inspected a large number of shore anglers, bait collectors and fishing vessels both at sea and on the river. All transgressions were dealt with and those guilty fined. The Night Fishing Ban has been in place for more than seven years now and yet we still encounter fisherman who claim to be unaware of the regulation. Please ensure you are aware of the rules and regulations of South African estuaries before harvesting living resources therefrom.

Follow us on your favourite social media platform to see what we are up to daily!

Tortoises, Terrapins and Turtles

Tortoises, turtles and terrapins all fall under the order Testudines (or Chelonia). Their shell actually forms part of their rib cage and vertebral column (ribs and spine fused to bony plates beneath the skin which puzzle together forming the hard shell). This means that the shell can’t be removed or separated from the rest of their body. The limb bones are altered as well as their pelvic and pectoral girdles positioned within the rib cage due to the shell's shape. The shell of testudines is referred to as a carapace. The shell is covered in scutes (horny plates made of keratin) which protect it from bruises and scrapes. Some Testudines lack scutes and have a skin covered carapace such as leatherback sea turtles, softshell turtles and pig-nose turtles. As the tortoise, turtle or terrapin matures the carapace grows outwards and expands like growth rings on a tree. Turtles generally have brightly coloured and patterned carapaces helping individuals recognize others of the same species from a distance.

Most testudines are sexually dimorphic meaning sexes of the same species will look slightly different. Males have a concaved plastron which allows them to mount females to mate. Females are generally larger than the male in most species.

Testudines have very interesting reproductive habits. Females generally lay their eggs in a moist yet sunny spot and cover the eggs with sand or marshy matter (leaves) for incubation. It takes 3 to 5 months for the eggs to hatch depending on the species and the time period in which the eggs were laid. Testudines’ eggs enter a condition called diapause where embryonic development may slow. Autumn

laid eggs go through very little embryonic development during winter and hatch just a little earlier than those laid the following spring. Clutch sizes also vary between species; sea turtles lay the largest clutches. Most testudines sex is determined by the incubation temperature; high temperatures (31 to 34 degrees Celsius) produce females and lower temperatures produce males. Nests

in sunny areas will therefore result in more females than those laid in the shade. Climate change threatens the natural sex ratios of testudines’ species.

General behaviour of testudines varies between tortoises, terrapins and turtles.

Turtles

Females usually only breed every 3 to 4 years. There are no known turtle species that cares for their young, the hatchlings fend for themselves as soon as they are born. Female turtles come to shore after mating and lay eggs in a dug out sand hole. She will then cover the hole with sand and return to sea. Sea turtles can lay up to 800 eggs in a season, generally multiple clutches of 50 to 120 eggs. The eggs need to be laid on land (preferably in the sand) as the embryos breathe air through a membrane in the egg as it develops, they have no chance of hatching if continuously submerged in water. The eggs hatch after 45 to 75 days and the hatchlings instinctively move towards the water. Turtles reach maturity between 20 and 50 years old and can live in the wild to more than 80 years old. Newly hatched turtles are carnivorous, feeding on organisms on the water's surface. Adults and immature juveniles of most turtle species are herbivores often found grazing on seagrass meadows, but levels of carnivory differs between species. Leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) feed almost exclusively on jellyfish and is the only pelagic turtle that feeds in the open ocean, in extreme depths (up to 1 200 meters) and at the surface. The Loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) is often found along coral reefs and rocky areas feeding on conches and other hard shellfish. The Green turtle (Chelonia mydas) is known to enter estuaries and shallow lagoons to feed on sea grasses.

Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta)

One of the rescues from Witsand, now happy in its new home - the Two Oceans Aquarium.

Loggerhead turtles are very large reaching almost a meter long and weighing between 100 and 150kg. Adults have a smooth elongated shell tapering at the rear whilst juvenile shells aren’t as smooth. These turtles have a very broad head with strong jaws. Males have longer tails and bigger heads than females, they also have a strongly curved enlarged claw on each flipper. Hatchlings are uniformly brown on their carapace and plastron with a darker head, neck and flippers. Adults are red-brown at the top of their heads and carapace, with white edged scales. Their skin is a light yellowish grey.

Loggerhead turtles migrate across open seas and feed in bays as well as coastal waters and reefs. They are also known to feed in lagoons, salt marshes and river mouths. This species has been spotted 240km from land. Loggerheads are more common along the east coast than west coast of South Africa.

For the first 3 years of a Loggerhead turtle's life they just drift in surface water, eating comb jellies, bluebottles and foraging in shallow coastal waters. This species has extremely strong jaws to crush hard bodied organisms and reef invertebrates (e.g. jelly fish, squid, snails, whelks, mussels, oysters, barnacles and crabs to name a few). They will also feed on fish and young turtles if they manage to catch them. In cold waters they are able to remain submerged for up to 7 hours at a time only surfacing for 7 minutes to recover (becoming semidormant). Loggerheads take 10 to 30 years to mature (reach maturity when their carapace exceeds 60cm).

Loggerhead turtles migrate far distances between feeding areas and nesting beaches. Males court females by circling, biting her neck and shoulder. They mate at the surface of the water; females generally remain completely submerged. Mating can last 3 hours. Females will mate with a few males, storing their sperm. Multiple males may be father to a single clutch of eggs. Females will nest above the high tide mark of temperate zoned beaches. The nests are generally dug during high tide at night. Within a breeding season a female can lay up to 500 eggs, in clutches of 120 eggs every 11 to 15 days. The eggs incubate for 47 to 66 days; hatchlings usually emerge at night being just under 4cm. Most females return to lay eggs at the same spot after 2 or 3 years, but some may only breed again after 8 years.

Tortoises

Tortoises differ from turtles. Female tortoises of larger species such as Leopard and Spurred tortoises lay 50 to 70 eggs a year, in multiple clutches per season. Smaller species lay a single clutch of up to 10 eggs per season. Larger species do however take longer to mature and reach sexual maturity than the smaller species. Some species (like the Geometric tortoise) living in fire-prone biomes will lay their eggs underground during the fire season. Fire is a natural factor in the fynbos biome and renosterveld. Some biomes need fire to maintain its plant biodiversity. Adults will still die (most probably) in the fire but the eggs will be safe, where they'll be able to hatch. This ensures that the tortoise population overall is not at risk. The tortoises generally lay their eggs underground during the summer and autumn when fire is most common. Terrestrial testudines are able to retract their legs and head into their shell if they feel threatened.

Most tortoises are herbivores - grazing on grasses, leafy greens, weeds, flowers and some fruits. Some will also eat various insects. Tortoise species are generally distributed according to the vegetation type. Tortoises are thought to be essential seed dispersers. They don’t chew their food, making them inefficient feeders. Tortoises also don’t have specialized gut vats and bacteria – this means that they have to eat a large amount of plants and their faeces are full of undamaged seeds. They often defecate (or poo) in bushes where seeds have a high chance of germination compared to in open land.

All tortoises fall under the family Testudinidae; there are 7 genera and 58 species. Africa has the richest diversity of tortoises in the world.

Angulate tortoise (Chersina angulata)

The Angulate tortoise is endemic to the tip of southern Africa. They are medium sized tortoises; along the Western Cape they may reach over 1.5 kg. Unlike most other tortoise species, males grow larger than females. Mature males are more domed than the females, they also have a single gular that protrudes beneath the head. Angulate tortoises have weakly hooked beaks and 5 claws on each foot. Their scutes are a light straw yellow and dark brown with black edges. Older individuals have a smooth shell almost uniformly dirty straw coloured. Hatchlings carapace is flat with a greater curved width than length.

Angulate tortoises are often found in sandy coastal areas and coastal fynbos (in the west, mesic thicket in the east). They are herbivores that feed mainly on grasses, succulents and annuals. Their optimal body temperature is between 14 and 29 degrees Celsius, but can withstand up to 40 degrees Celsius. Above and below their optimal body temperatures the Angulate tortoise isn’t really active.

This tortoise species generally lives in high densities where the vegetation is able to support it. Males and females have similar home ranges of up to 2 hectares (often smaller in moister environments). Males don’t defend territories but rather try prevent each other from mating with the females. Males fight by ramming into each other and using their enlarged gulars to overturn the opponent. Mature males often develop a low shell that flares at the front and back to lower the centre of gravity making it difficult for opponents to overturn them. Mating is long and noisy making it difficult for smaller males to mate discreetly. As a result of only victorious males getting an opportunity to mate, males grow larger than females in the angulate species.

When the soil is soft after rainfall females use their hind legs to dig a shallow hole about 10cm wide. Females can retain eggs for up to 212 days before being laid if they in a dry period. They lay only 1 and rarely 2 eggs in the nest, the whole process can take up to 3 hours. The female will trample down the soil over her egg to camouflage the area. She will then immediately prepare another egg after laying one, angulate females can lay up to 6 times a year. Eggs incubate for 90 to 200 days depending on the season and eggs begin cracking up to 10 days before hatchlings emerge. Hatchlings are just over 3cm long and only reach sexual maturity after 9 to 12 years.

Angulate tortoises are predated on by baboons, secretary birds, sea gulls, crows and rock monitors. Fiscal shrikes also pierce hatchlings on tree thorns and mongoose feed on the eggs. Angulate tortoises have a large risk of nest predation from mongooses and jackal.

Parrot-beaked tortoise (Homopus areolatus)

The Parrot-beaked tortoise is a smaller tortoise with an average size between 10 and 13cm, females reaching 16cm (females grow larger than males). They don’t have a hinge on their shell. The Parrot-beaked tortoise has deeply grooved scute margins with the centres indented. They have strongly hooked beaks with a weakly serrated edge. Their nostrils are high on the swollen snout. Large scales overlap the 4 claws on their front legs. Mature males have longer tails. Their shells vary between orangish and greenish. Parrot-beaked tortoises generally have a yellowish olive shell with red-brown patches. The females and juveniles usually have darker margins. In breeding season this tortoise species develops swollen bright orange nasal scales.

Parrot-beaked tortoises are endemic to South Africa, having a very small distribution range. They occur in coastal fynbos, karroid broken veld and open mesic thicket habitats. This species won’t forage in the open, but prefers sunny spots under thicket cover, in bushy grasses, under rocks or in abandoned animal burrows. Parrot-beaked tortoises climb up steep surfaces with ease.

Males fight extremely aggressively often causing severe bight marks. Fighting can last over an hour, they bite the anterior edge of each other’s shell and push against each other. The dominant male often chases after the loser. From May to November females lay clutches of 1 to 3 eggs in small sandy holes. Some females lay an extra clutch. The small eggs take 150 to 300 days to hatch. Hatchlings are about 3cm and weigh between 4 and 8 grams.

Terrapins

Most terrapin species lay a single clutch of eggs per season. South African terrapin species have adapted to the generally dry landscapes with irregular rainfall. Many wetlands in South Africa are temporary or seasonal. During dry periods some hinged terrapins dig underground and lie dormant until it begins to rain again (behaviour known as aestivating). Their gut is first emptied of all food and waste before going dormant, then their heart rate and blood circulation reduces. As freshwater wetlands fill up and swamps flood, terrapins emerge from their temporary burrows and continue their lives. Soft shell terrapins don’t aestivate and therefore only live in areas with permanent water like rivers and lakes. Some terrapin species have even adapted to withstand brackish water and live in lagoons or estuaries. They are able to survive short periods in the sea when washed out with the current, this has allowed them to colonize the lower reaches of rivers. Females lay their eggs on land. Terrapins are also often seen basking in the sun on land near the water’s surface. Terrapins are generally omnivores mainly feeding on invertebrates, some species even prey on fish and frogs. Many terrapin species rapidly gape their mouth to create a suction to catch prey. The Marsh Terrapin (Pelomedusa subrufa) has a light shell allowing it to ambush frogs and catch birds drinking at the water’s edge. Terrapins soften their prey crunching it with their jaws before swallowing.

Testudines lifespan is similar to human beings, although some individuals have lived longer than 150 years. The oldest recorded was a radiated tortoise (Geochelone radiate) that lived to 188 years old under the Tongan royal family’s care.

Marsh terrapin (Pelomedusa subrufa)

The Marsh Terrapin is a fairly large species reaching 35 cm, males grow larger than the females. Males have longer tails and a flatter narrower shell than females. They have a very flat, thin shell and a large head (head is darker on top and paler below). This species has 2 tentacles under the chin and webbed hind feet. The Marsh Terrapin shell is olive/dark brown above with a black edge and pale margins.

The Marsh terrapin prefers still water or very slow moving rivers. They are often found in temporary wetlands. This species is the most widely distributed Testudines in Africa. They thrive is shallow, temporary water bodies even without vegetation. Don’t usually occur in the same habitats as crocodiles as their thin shells don’t protect them from predation.

The Marsh terrapin isn’t active at temperatures below 17 degrees Celsius and may be seen basking in the sun on land or emergent rocks or by floating on the water’s surface. During the dry periods they burry themselves in moist soil often far from their aquatic habitat, going into aestivation.

Marsh Terrapins are omnivores, feeding on almost anything they come across. They eat insects, frogs and aquatic plants. They are also known to ambush and drown birds that come to the water to drink. They face a risk of being run over when migrating to new areas after rainfall. Due to their unpleasant musky smell, few people eat them. Some populations have become locally extinct due to oil spillages.

Marsh Terrapins mate in the water and 10 to 30 (sometimes up to 40) eggs are laid in a flask shaped pit. After 90 to 110 days the eggs hatch. The hatchling emerge after the ground has been softened by rain and measure between 2.5 and 3.8cm, weight 8 to 10 grams.

Conservation and threats

With the exception of sea turtles, most Testudines found in South Africa are endemic, meaning they don’t naturally occur anywhere else in the world. For this reason alone, it’s important that we conserve and protect them. Only 2 of South Africa’s endemic species are considered endangered – the geometric tortoise and the spurred tortoise. The Geometric Tortoise is one of the worlds most threatened species, they occur in very low densities (2 to 3 tortoises per hectare) in the small patches of coastal renosterveld. Renosterveld itself is under stress, only 5% remains and the rest has been urbanized or converted into vineyards and wheat fields.

All 7 turtle species are listed on CITES Appendix I (a list of species threatened with extinction, trade of these species is only allowed in exceptional circumstances). Turtles have a lot of threats, they often killed for their meat when they come to shore to nest, many drown in shrimp nets or killed on fishery longlines and others choke on swallowed plastic.

The main threats to Testudines are being used for bush meat, habitat loss, electric fences, pet trade, crossing roads, fire and alien introductions. As urbanization increases in areas that were previously undisturbed the exploitation of tortoises for meat increases. Tortoises are very easy to collect and their bones, shell fragments and meat is used in many tribal systems such as the San of the Kalahari and the Hadza of Tanzania. Also in modern times, greedy people with no interest in sustainable use have turned the

bushmeat (including tortoise meat) trade into a commercial venture. The new prosperity in China means a huge demand for tortoises for meat and pets. Habitat loss poses a huge threat to tortoise populations. A large amount of natural habitats particularly in the southwestern cape has been cleared for vineyards and wheat fields. Many areas are also purposely burnt too regularly to promote

grazing for cattle. Wetlands where terrapins inhabit are also under threat from siltation resulting from erosion (which is cause by overgrazing), pesticide pollution, alien plants clogging water ways and eutrophication from fertilizer runoff. Wetlands are also often drained for agriculture use. Electric fences also cause many deaths of tortoises; one shock isn’t fatal but continual cycles will cook the tortoise alive in its shell. Although tortoises can endure neglect, they have sensitive climatic requirements. Most pet tortoises die within a year of being captured due to a lack of sunshine or being cold or stress related illnesses. The exotic pet trade is a growing industry (whether it is done legally or illegally). The exotic pet trade goes hand in hand with alien introductions. Many people release their exotic pet once it gets too big to take care of. One example is the American Red-eared Terrapin (Trachemys scripta) – over 2 million are exported from the USA every year. No breeding populations of the Red-eared Terrapin has established in South Africa yet, but it is a huge problem in Israel, Taiwan and other European Countries. They have been banned in many countries due to the risk of them establishing an alien population.

Living along the Breede River means we are lucky enough to be in the heart of many Testudines’ species habitat. It also means it is our duty to conserve and protect them. Farmers must take care not to let their cattle overgraze wetland areas and ensure that areas aren’t burnt too frequently. Fertilizers should be prevented from running into the sensitive wetland areas. Take care when diving through tortoise territory (eg the whole of Witsand and the Breede River area). If a turtle hatchling is found on the beach bring it in to the Lower Breede River Conservancy Trust. Don’t participate in the exotic pet trade, tortoises are better off in their natural habitat and not as a pet. Every life matters and counts towards preserving the Testudines’ populations in the area. It takes effort and awareness to conserve the natural life found among us. It takes a long time to increase the natural population numbers of the endangered species, but as we know slow and steady wins the race.

REFERENCE LIST

Branch, B., 2008. Tortoises Terrapins & Turtles of Africa. Cape Town: Struik Publishers.

Keller, D., 2021. Sign in | Pet turtle, Turtle habitat, Turtle. [online] Pinterest. Available at:

https://za.pinterest.com/pin/376332112606437483/ [Accessed 20 April 2021].

Lew, M., 2021. Parrot-beaked tortoise. [online] Animalz-world.blogspot.com. Available at:

http://animalz-world.blogspot.com/2013/11/parrot-beaked-tortoise.html [Accessed 20 April 2021].

Pecor, K., 2003. Testudines. [online] Animal Diversity Web. Available at:

https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Testudines/ [Accessed 20 April 2021].

Tuma, M., 2021. [online] Hardaker.co.za. Available at:

http://www.hardaker.co.za/r-angulatetortoise7.jpg [Accessed 20 April 2021].

Wilkin, D. and Gray-Wilson, N., 2016. Welcome to CK-12 Foundation | CK-12 Foundation. [online] CK-12 Foundation. Available at:

https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-biology-advanced-concepts/section/16.28/ [Accessed 20 April 2021].

In the data

Monthly routine monitoring

April bird counts

Our monthly bird count was conducted on 28 April. After the mist had cleared we set off to record every bird from the mouth to the pont. The weather was overcast and it threatened to rain all day, but the birds were still plentiful. Over 1000 birds were recorded, of which the most common were Yellow-billed ducks (234), Egyptian geese (180) and Sandwich terns (176). We were fortunate enough to spot a Denham's bustard in a field close to the pont.

April water quality

The water quality run revealed very similar conditions compared to March in terms of salinity. The mouth presented the most saline conditions (34.11 PSU), and fresh water was reached closed to Lemoentuin - 33 km upriver. The river was a lot cooler than in March, averaging 18.38°C.

Jetty and slipway policies

CapeNature and the Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (DEA&DP) are responsible for the regulating, operating, and legalisation process of jetties, slipways and other structures below the high water mark (HWM) in terms of the Sea-Shore Act, 1935 (Act No. 21 of 1935), the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998) and the Environment Conservation Act, 1989 (Act No. 73 of 1989).

Monitoring along the lower Breede river does take place. Management of structures built below the high water mark is necessary because of aesthetic, safety, and ecological reasons. These structures have hydrodynamic effects, altering the flow of water and can therefore cause accelerated erosion and deposition of sediments. Often natural habitats are destroyed in their construction. After which these disturbed areas are more susceptible to invasive alien vegetation becoming established. We have seen this facilitation upriver, where water hyacinth and parrot weed persist. Like with all man-made structures, their impacts are cumulative, and so compliance with jetty and slipway policies helps to ensure the long-term sustainability of our river banks. Alongside is a summary of the conditions and structure specifications that should be adhered to by property owners.

Slipways:

- One slipway per property

- Slipway follows contours of riverbank and river bottom

- Must not exceed 3.5 m in width

- No longer than 6 m below HWM

- A reflective number plate indicating the property number needs to be fixed to a pole and planted in the ground next to the slipway or on the jetty belonging to the same property

Jetties:

- Usually one jetty per property (floating jetty preferred)

- Constructed of unpainted hardwood/building pine

- No roofs or rooms

- No longer than 6 m below HWM and no further than 1 m beyond reed line

- Gangways no wider than 1,5 m and platform no bigger than approximately 4 m x 3 m

- Pontoons constructed of non-corrosive material

- A reflective number plate indicating the property number must be attached to the jetty in such a way that it is visible from the river

Please do not clear more than 1 m of vegetation (i.e. reeds) on either side of your slipway and/or jetty gangways. We have witnessed an increase in reed bank removal by land owners without permission. The riparian vegetation provides key ecosystem functions in terms of water quality and bank stabilization, as well as provides an important habitat for bird species and even aquatic invertebrate species below the surface.

Indigenous tree alternatives

The eradication of alien vegetation is a difficult task. Some plants are notoriously persistent, such as Acacia and Eucalyptus species, whilst others you might not have known were alien. We have noticed that many properties along the river have planted alien trees, and whilst their effects on the ecosystem are still minimal we would like to propose some indigenous alternatives instead. Alongside is a list of both alien and indigenous trees, which can be used by property owners to keep future landscaping eco-friendly. The indigenous plants that are included are also indigenous to the area, making them suitable for the climate and wildlife.

Milkwood removal

Under the National Forests Act of 1998 (Act No. 84 of 1998) cutting or pruning of white milkwoods (Sideroxylon inerme) requires a license, except if less than 25% of the crown is pruned, but not for the topping of such trees, and not for new development or redevelopment (exemptions published in Government Gazette no. 773 of 27 August 2007).

Photos of the month

The photo-of-the-month competition is an initiative which the LBRCT is promoting whereby members of the public can send us their photos of anything related to the natural beauty of the Breede River! Please send your photos to info@breede-river.org.

We would like to thank Jacque Smit for sending us his beautiful photographs! All landscape and bird photographs in this issue are his work.

Brown-hooded kingfisher

(Halcyon albiventris)

Knysna woodpecker

(Campethera notata)

Spotted eagle-owl

(Bubo africanus)

Turtle Alert!

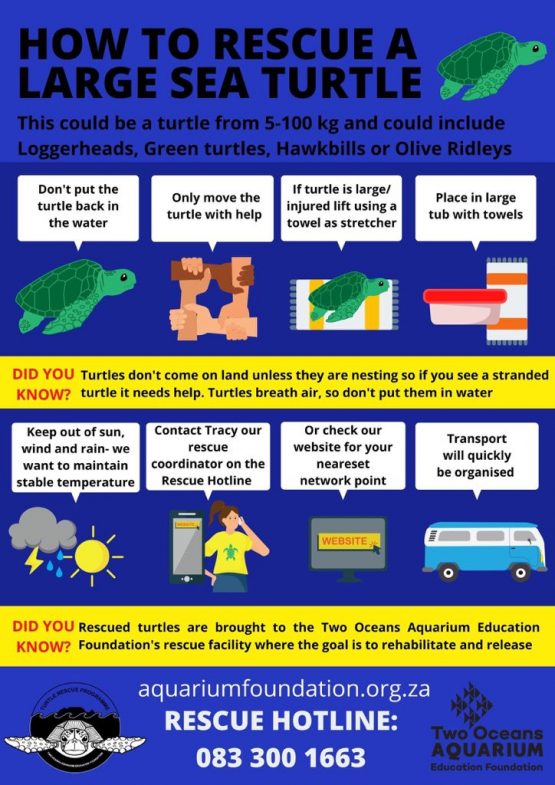

Turtle season is upon us! Please be on the look out for turtle strandings along our beaches. Report any strandings to the LBRCT (028 537 1296) and Two Oceans Aquarium (083 300 1663) as soon as possible. Here are some informative posters from the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town.

Thank you for reading

We hope you enjoyed this months' issue. Should you have any feedback, questions, or matters you would like us to cover in a future issue, please do not hesitate to write to us at news@breede-river.org.